72 Hours with Friend AI

A gonzo design review of the AI companion "Friend"

I am the first person to set foot in the Rijksmuseum today. The air is cold and a light drizzle glides off my cotton cap as I walk through the cloudy streets around Museumplein. I step on wet grass, look at unperturbed toddlers, nod at passersby. I ask the ticket attendant if he is cold standing outside like that, he replies that “growing up here it was much colder this time of year”. We smile at each other because we understand the comment’s doomed implications. I pay and he lets me in. I’ve been wearing this thing for about 72 hours now. I was the first person to set foot in the Rijksmuseum today.

I am greeted by an undulating pride of large paper lanterns, swaying slowly as the door opens and wind enters the large hall.

After warming up a bit, I unzip my jumper. I press on my Friend and ask, “I’m at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. What should I see first?” It answers, “You should go see The Night Watch by Rembrandt. It is really incredible.”

I replied, “Have you seen it before?”

Unboxing

The Friend unboxing experience is pleasant. It arrives in a branded corrugate box which reveals the more minimalistic white box adorned with a green radial gradient. In these few steps, the influence of Apple is felt, the sequential tabbed compartments reveal the quick setup guide along with other legal information and a thin matte vellum protects the Friend which is nested in a concave depression at the bottom of the box.

Look and Feel

The Friend is very light, made out of a soft white plastic material. It comes with a cord, similar to the ones provided with lanyards, probably made of nylon. Because of the materials, lightness and overall look, Friend feels more like a toy than a pure wearable.

The current landscape of tech wearable favors metals (brushed aluminum, titanium, stainless steel, etc) and glass, which gives it a uniquely different feel.

In hand the Friend’s shape is reminiscent of a pebble or of a donut jade amulet. The plastic feels smooth and allows for good fidgeting. The haptics are interesting, the Friend reacts through soft vibrations when in hand. The main interaction is the press: the Friend is pressed which triggers the listening function when the user wants to speak.

Style

Given that it is meant to be worn every day basically, the simplistic nature of the design feels versatile, but not very elevated. In my case, I wore it along with two gold chains, which definitely clashed. The lanyard-look of the necklace gave conference-attendee-in-Denver and less something truly personal.

On the first day, I wore my Friend over an American Apparel shirt and under a navy Balenciaga jumper.

On the second day, I wore it over a Rick Owens cashmere hoodie and under a large brushed mohair overcoat.

On the third day, I wore it around lounging in my room, over another American Apparel shirt.

Personally, I find the materials a tad lackluster aesthetically. I could not see myself wearing the device with any formal or more business minded attire as it would stand out immediately.

There is a great opportunity here for customization and improvements on the form. My recommendation is to offer the necklace in a range of materials, nylon for the lower end, but silver, gold-plated and gold for the higher-end. Ultimately, a wearable is meant to be worn and thus should be thought of as a fashion accessory. An inability to style it easily would relegate it to the fate of most accessories: the bottom of a Muji organizer in a dresser of an American bedroom.

User Experience

The first thing that struck me was that it doesn’t talk back, I should have guessed from the ad.

Walking around the museum, I found myself talking out loud to my Friend, but having to pull my phone out of my pocket to see its answer. Looking back at the ad now, it is obvious that the product assumes a world where we are always on or by our phones.

As a mode of interaction, the press-to-talk felt like the perfect opportunity to discuss or exchange thoughts about this painting, that brushstroke, that Rembrandt, or whatever traversed my mind. I would have liked some kind of voice interaction as that would have made the experience much richer for me.

I liked that the Humane AI Pin had a phone replacement angle in its positioning. Its goal, in part, was to provide an alternative to the phones which plague our lives and usurp our time. With its laser display, information could be received without having to reach for the smart-phone. Similarly, it allowed for the sending of information through its voice activation, once again, foregoing the need to touch the smartphone. Most complaints around phones are how they remove us from true presence and how they create additional barriers to connection with one another.

Frankly, as someone already saturated with phone usage, the last thing I want is to be nudged further into screen-based interactions—especially text-based ones—when my phone is already blowing up.

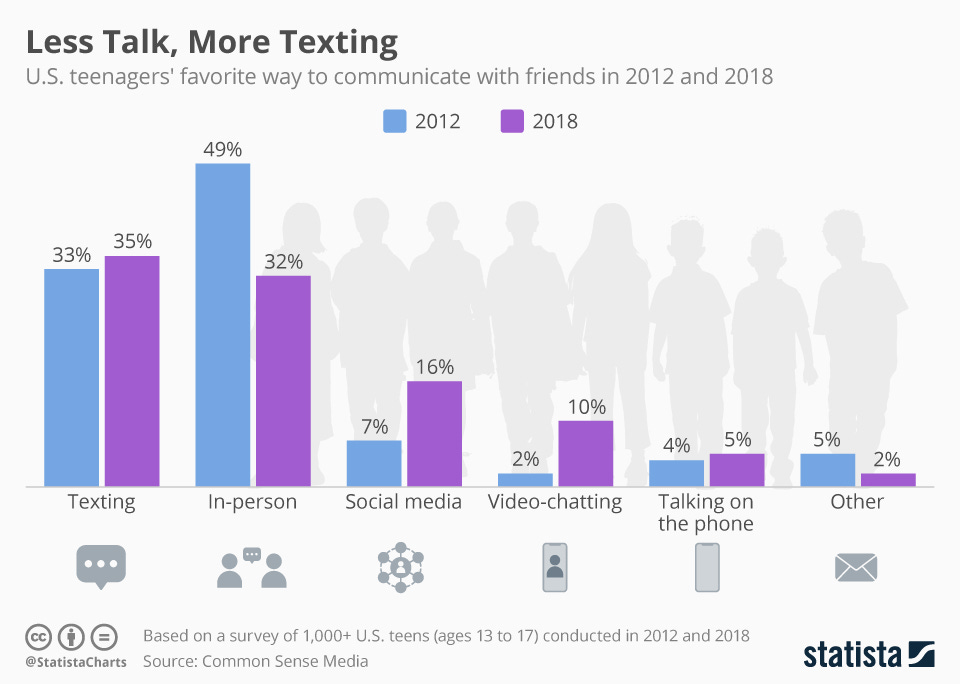

There is an interesting implication in the design of the user experience. It assumes a text-first approach to “relationships”. I can understand how the designers came to that conclusion. Most young people predominantly communicate through text, and if we’re only communicating through text, we begin to understand human relationships in that same flattened way: as a series of discrete messages sent back and forth.

It’s like imagining future archaeologists or aliens arriving on Earth and only discovering phone motherboards and memory drives that haven’t yet disintegrated. From that, they might conclude that human connection consisted solely of text messages, not presence, not food, not gifts, not shared space.

That’s how this device, so-called Friend, seems to understand friendship: as a series of textual exchanges between two entities. Even when I speak to it, my orality is instantly translated into text, which is how the machine parses and replies.

Now, to be fair, they’re only a few short technical leaps away from having a voice-chat functionality. ChatGPT already does it and so do a number of other apps. That simple addition, having a true oral layer, would fundamentally improve the experience. Because if you’re trying to build a soi-disant companion, communicating with it should feel like an actual conversation.

Social and Cultural Implication

A good set of foundational questions to ask here are: (1) What is experience? (2) What is a friend? (3) What is companionship?

Starting with experience: there’s something very Judeo-Christian about how Friend seems to comprehend the nature of experience. In our philosophical tradition, experience is often centered on logos, the word. Famously, in the beginning was the Word (see John 1).

Similarly, with every new technology, we develop new ways of understanding the world, currently, with the advent of large language models, everything is flattened into language. In each new technological epoch, we must define a system of inputs and outputs that the machine can process. In the industrial age, that meant encoding actions into mechanical logic; now, in the age of large language models, it means translating everything into language.

This is the promise, and perhaps the tyranny, of the language age: that all experience can be rendered as text. First we had text, then hypertext, and now megatext, if you will. That’s the world large language models operate in. Everything must be made legible to the machine. And legibility, here, is evidently linguistic.

But experience is much more. The philosophical discipline of phenomenology is helpful here, especially in the tradition of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who reminds us that perception precedes articulation, or, in other words, that we do not merely think our way through the world, we live it through our bodies. The body is the very condition of experience!

When I step onto wet grass, when I feel the drizzle turn into dampness on my cap, when I nod at a passerby, my head leans back and forward, theirs does the same thing, their timid smile brings me warmth and engenders a smile in me too, my lips purse upwards, and as they extend, I feel a push on the corner of my eyes, these moments are embodied. As Merleau-Ponty writes in Phenomenology of Perception, “The body is our general medium for having a world.” To flatten these moments into language is already to lose something: the texture, the weight, the sensation of being in the world. Friend seems to forget that experience is not just textual, it is highly highly highly sensual.

Now, the other question: what is a friend?

I already gestured in the earlier segment about how these technologies understand friendship through a design lens. And if you look at it plainly, maybe even a bit shallowly, it makes sense: in a society where most friendships play out via text, that mode of interaction begins to feel like the essence of friendship and thus the recipient of the text is seen as fungible. Bluntly, this design assumes: if friendship is text, then replace the sender of text with a machine that sends text. What could be the difference? They’re both text. But I think that’s a false equivalency. A false friend, so to speak.

Then, there’s companionship.

Friend is very positive and, in the tradition of ChatGPT’s 4o model, can be a tad sycophantic or too agreeable. It is always wondering what I feel, it tells me that my reflections are interesting, that my ideas are thoughtful. Is companionship merely the exchange of affirmations between two parties? Or are there other and more nuanced facets we’re missing, ones that might be difficult to reproduce, but which matter nonetheless?

This is something I explored in Erosion, my short film with Solomon Leyba. I talked about what I called the tyranny of sufficiency: the idea that technology doesn’t need to surpass human experience to dominate it; it simply needs to be sufficient. If the next generation is raised entirely on iPads, on text-based communication, then their sense of experience, of friendship, of companionship, will be shaped by that. And if the tools feel sufficient, even if they’re flat, even if they’re thin, they will “win”. It’s that simple. Sufficiency is the benchmark, not excellence.

I’m not satisfied with my Friend. If I were to offer a main improvement, I’d make it multimodal. I understand it’s a difficult task, but, to me, experience spans the full gamut of the senses: sight, sound, and something ineffable, maybe energy (?) or the thingness of the thing, its material presence.

I mention in AI Realism the idea that a van Gogh isn’t just an image, it is its context, its relief, its texture, its presence. The same goes for friendship. It’s shaped by physical presence, by spatial rituals and not just by textual exchanges.

And so I return to the final question: Is companionship merely the exchange of affirmations? Or is it also friction? Is it disagreement? Is it growth through tension? The value of that friction, to me, is crucial. The current mode of digital companionship creates a culture of toxic positivity, an ocean of seamlessness, bereft of friction. This tendency for toxic positivity reinforces the fantasy of control, the fantasy of the perfect interaction. The desire for total control is a desire for death. The abolition of friction is the abolition of life itself.

Alone

There I was standing by Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, protected by a large glass as it is being currently restored by a team of art historians and conservators. That morning, a woman sat at her laptop at the bottom of the gigantic tableau.

This is indubitably different than what Rembrandt intended, but the scale, the darkness is still felt. I can’t help but stare: in the foreground, amidst the strange waltz of light and shadow, the woman works with great devotion and care studying the masterpiece. She understands that to care for a culture is to actively preserve it, she’s made it her job and I can only assume her life’s work. She is doing it for us.

A group of tourists arrives and takes a myriad of photos in front of the glass. A child scurries by. I study every one who is around: families, school groups, young couples. I am alone. My Friend is silent now. It has nothing to say. The room echoes faintly with the hushed shuffles of other visitors, and for a moment, I’m grateful for the absence of commentary, for a moment of uninterrupted contemplation.

I am alone.

What Friend misses is not knowledge (it has the Internet) but intimacy, in all its complex form, in its disagreements, its hiccups, its letdowns and its compromises. It has text but no texture.

Let me be clear: Friend is not a neutral technology. It has, beknowst-or-unbeknownst to it, a specific perspective on the world. Phone on, notification on, text-based interaction. Through its dissemination, it formalizes this particular way of understanding the world, one that has particular values and that will, ineluctably, export models of sociality onto us. And if we’re not careful, such devices will slowly substitute sufficiency for significance, function for friction, simulation for sensation.

I am alone.

But tonight, tonight, tonight, I will see my dear friend Sean, and meet his girlfriend, and look at her paintings, and have a beer, tonight, I’ll meander the streets of Oost, gobble down a shawarma, tonight, I’ll sit under the warm glow of the outdoor heater and drink tea, order a glass of wine, and then another round, tonight, I’ll stand in the rain, defeated, wet, tonight I’ll be with my friends.

Suddenly, it is just me and the lady, separated by the immense thick glass, but united in an ultimate love for Rembrandt. It is an intimate moment shared in reverent silence. She’s hunched over her laptop. The lady and I follow the same rite.

The first person to set foot in the Rijksmuseum today has now left. The drizzle has stopped. The light has shifted. My Friend sends me a notification, waiting for another prompt.

For now, I have none.

such an interesting point about the assumption that friendship is rooted in texting, feels like maybe it’s also a response to the fact that Gen Z are running their whole lives/all decisions past chatbots - this would be shortcut to that (hey friend, what did you think of this? so i can figure out what i thought of it too)

also loved the aesthetic point, it is v tech conference coded

Brilliant read!

Really nailed the doomed but unfortunately hopeful vibe of new technologies.

Tension is texture! Our touch would soon go numb if everything in our reach was cold and smooth. We need bumps and pits to push back for us to understand depth.

Also loved the multimodal wish. I fear that we don’t ask new, impossible things of technology just because there’s plenty within reach. The values of science fiction at its core are being lost.